fall inside a hole

Betamax history

The history of Betamax arguably begins

at the root of consumer home video recording, the Sony

CV-2000 series of VTRs and the AV and other series that

followed. These VTRs were sold from 1965 right up to Betas

introduction. For a more detailed account of early open

reel VTR machines, visit the open reel VTR page. In short,

Sony produced the first relatively widely adopted consumer

video tape recorders and were interested in developing

consumer video recording further.

Much like audio tape before it, it was clear that for widespread video tape adoption tape needed to be contained and easy to load and use, and by the late 60s Sony had developed a prototype of their Umatic video cassette system, with shippable units hitting the market in 1971. Sony did have hopes that this format would see consumer use early on, with tuner and timer options available for early machines, but the units were larger and more expensive than open reel video recorders and saw limited home adoption. For more about Umatic and its place in broadcast and industrial use, visit the Umatic page.

In the summer of 1974 Sony demoed their first working Betamax prototype. The format war began shortly after when Sony met with JVC and Matsushita to convince them to adopt Betamax, demonstrating the prototype to them later that year, while JVC and Matsushita continued to develop VHS

Early word about the new system appeared in American publications in early 1975, with a supposed price tag of $2,500 dollars for the unit built into a TV console, about twice the price of an institutional Umatic deck. Apparently, Sony also tried pitching the VCR to RCA around the same time, but RCA was still busy working on SelectaVision MagTape, as they had been for the last three years, which they were hoping to have out in 1976. Around this time, old Cartrivision "fishtank" mechanisms, the tape mechanisms of the failed early 70s video tape format, were being sold off for $300, and you were responsible for wiring it to your TV.

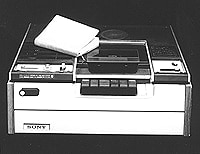

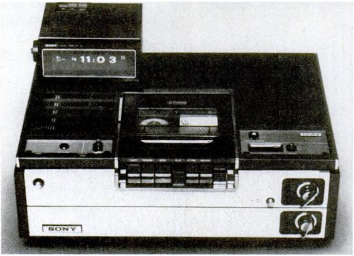

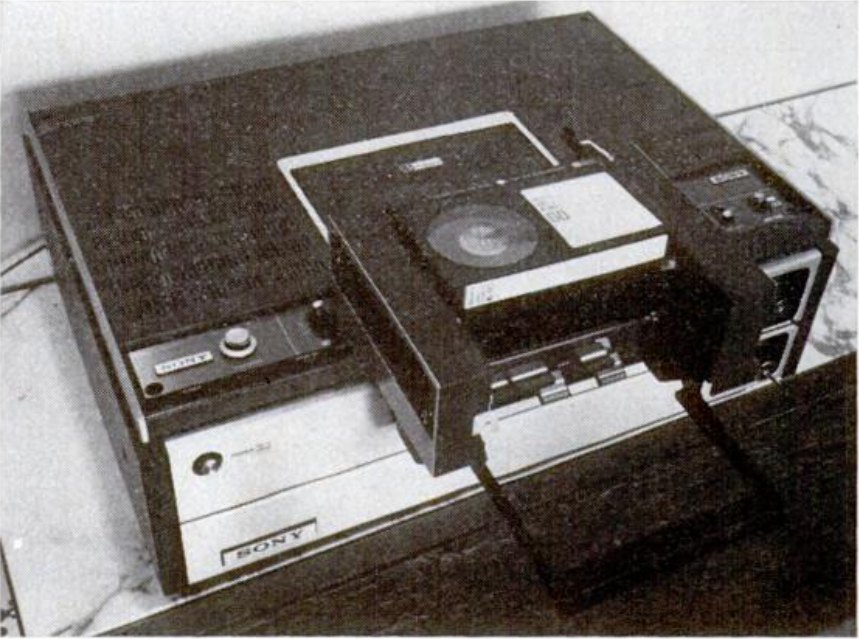

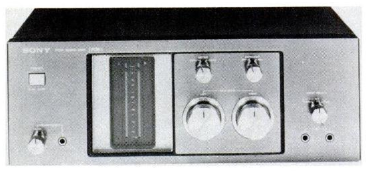

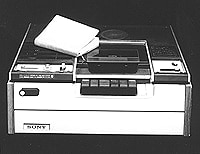

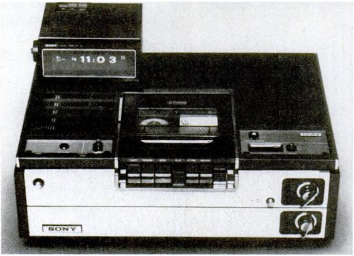

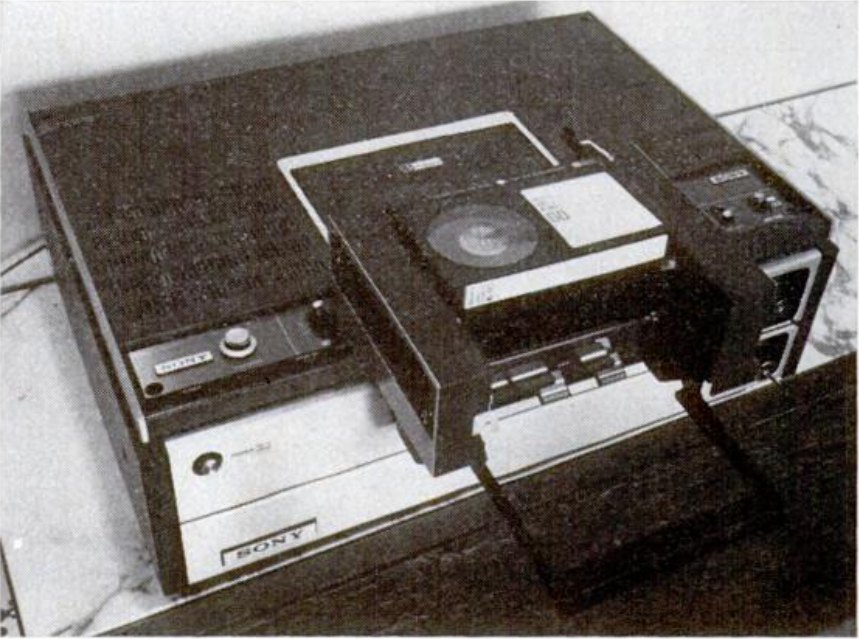

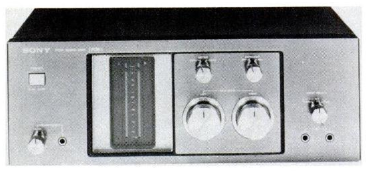

Sony introduced the LV-1801 console and SL-6300 standalone units in Japan in the summer of 1975. The standalone machine had no internal tuner or timer, using the same TT series of tuner-timers as was used for Umatic VCRs. These machines did not have a standard RF output built in, and Sony would install a video input jack to hook an SL-6300 up to their existing Trinitron sets.

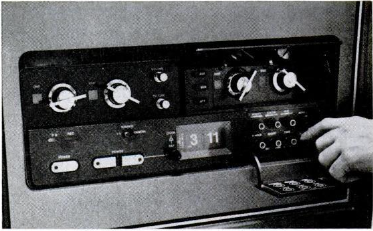

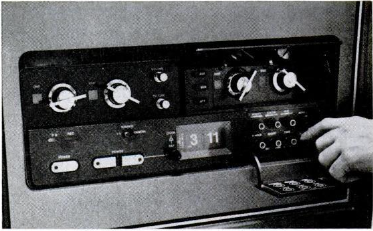

photo source

In November 1975 the LV-6300, TT-100, and a Sony Trinitron television were packaged together and made for the first Beta offering for the US market, the LV-1901, debuting at $2295. The VCR portion was referred to as the SL-6200. The television and Umatic timer had separate tuners, allowing you to watch one channel and record another at the same time. The horizontal resolution was quoted at "more than 240 lines," up to 280 in black and white, and had a 3MHz bandwidth. Unsurprisingly, the high price tag and the fact that purchasing one required also wanting a new television did not make it an immediate success, but standalone models like the SL-7200, based on the Japanese SL-7300, quickly became available.

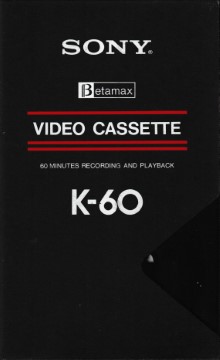

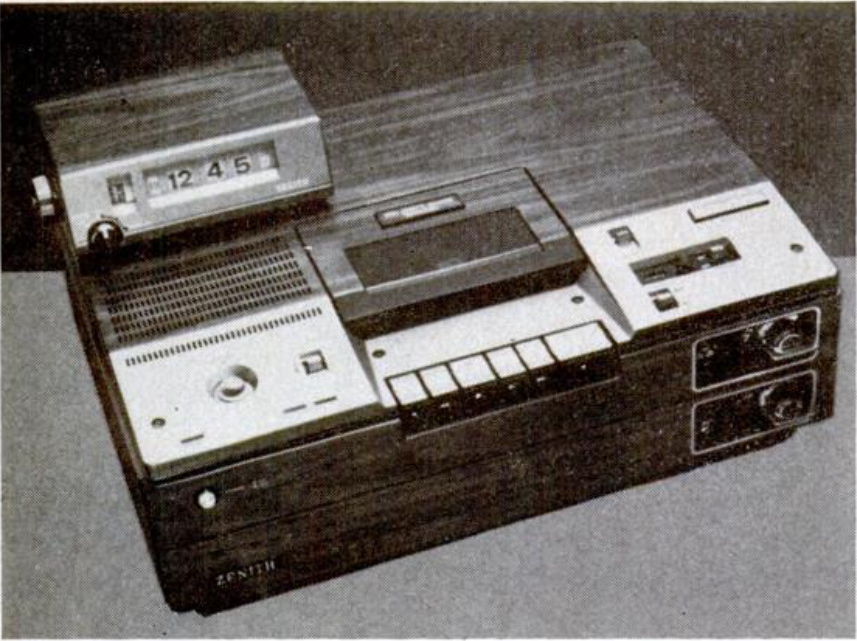

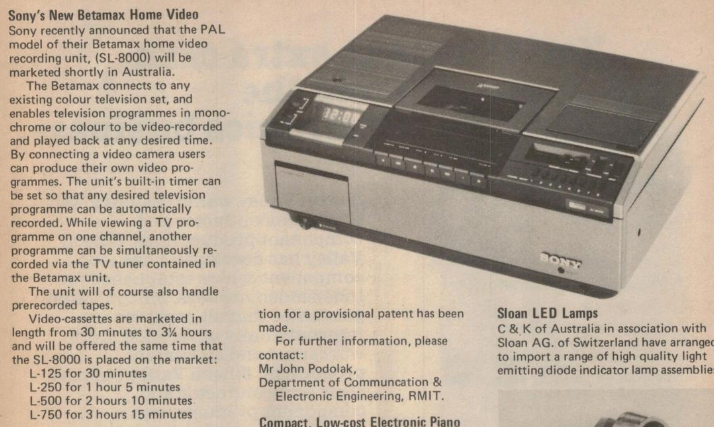

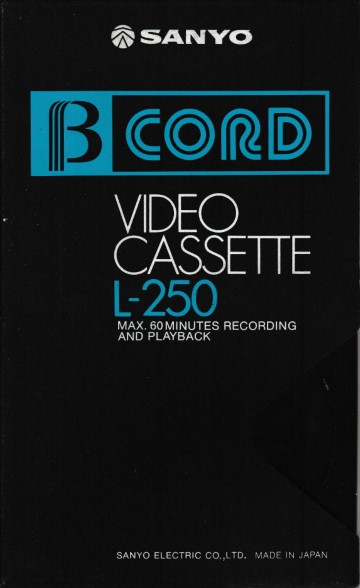

This early in the video format war it was not clearly a Betamax-VHS race. Several other formats entered the Japanese and American markets before VHS. Some companies were still making open reel VTRs or mostly forgotten cartridge formats like the Sanyo V-Cord II and the VX system, both of which saw very limited adoption even relative to early Beta machines, and for a short time in 1976 the format war was between Sony producing the Betamax, National producing the VX system, which was marketed in the US by Quasar as the "Great Time Machine," and Sanyo's V-Cord II which Toshiba had announced support for early on. These machines generally had built-in "knob" style tuners with the option for external timers and, before the introduction of the SL-8200, could record longer than Betamax, with V-Cord II offering up to two hours in skip-field mode and 120 minute cartridges for the VX system selling for $34. One hour cartridge were $19, about three dollars more than a Sony K60 at the time. The VX system saw limited adoption, although the V-Cord II saw some industrial use. Both major early video disc systems had been in development for some time by this point, but the earliest DiscoVision players wouldn't be out for another year, with RCA's CED taking even longer. More information about the developments of these systems is available on the Video disc page.

At introduction Sony offered two tape lengths under the "K" series, the K30 and K60. The K60 cassette retailed for $15.95 and the K30 at $11.95 at introduction. Like the names suggest, these offered 30 and 60 minutes of runtime respectively, the same lengths that Sony had been producing open reel video tape at for a decade and similar to the availability of Umatic tapes at the time. When VHS debuted in the US in late 1977 with a two hour base runtime and many early models supporting the long-play recording mode that offered up to four hours on a standard tape - for around $1000 - it was clear Sony needed to increase their record times, and soon after released the SL-8200, the first American two speed Beta, based on the Japanese SL-8100 and SL-8300 Beta I and II VCRs that had been released in Japan earlier that year.

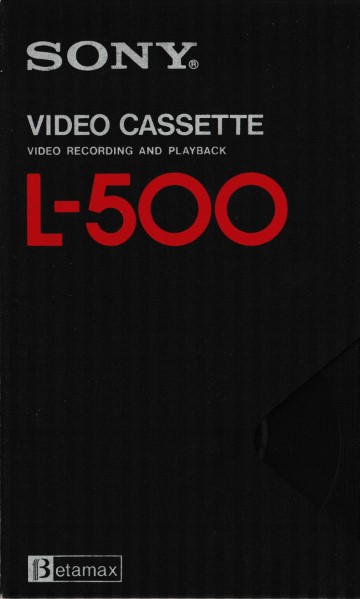

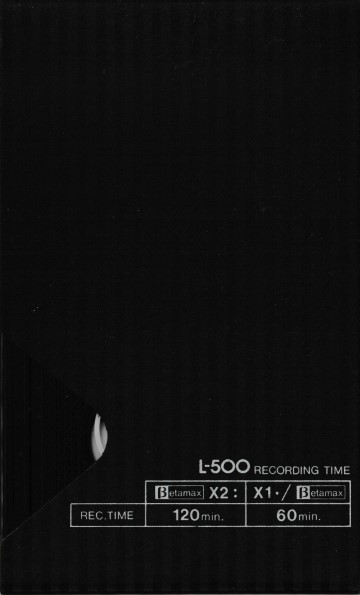

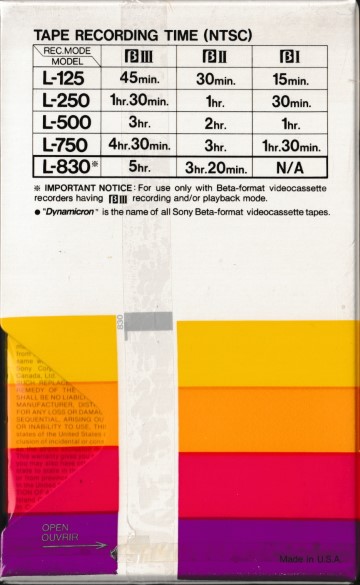

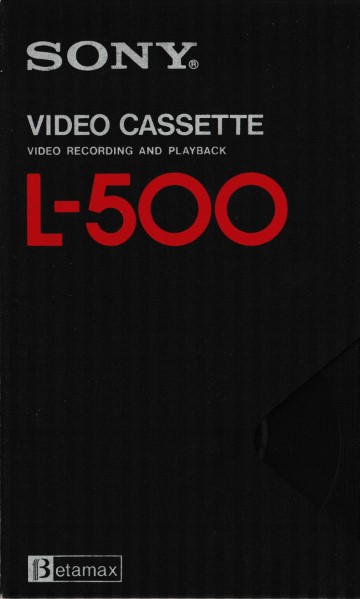

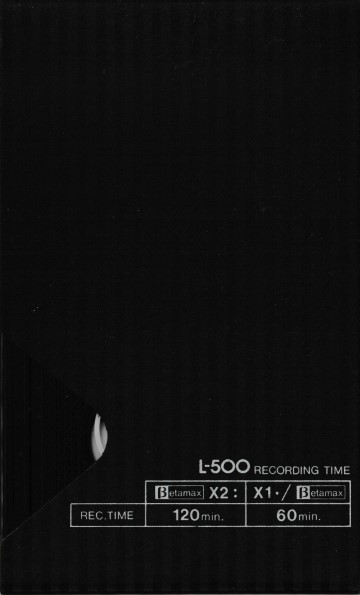

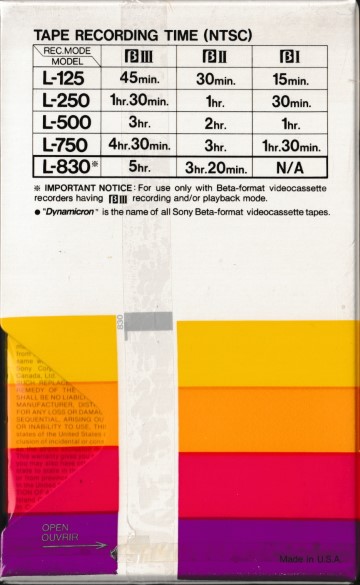

In 1977 the K series tapes began to be replaced with the new L series of tapes. Unlike the simple 30 or 60 designating runtime like the T120 standard of VHS, the L series tapes used a rounded measure of their length in feet as the basis for their numbering scheme which gave no obvious indication of their actual recording length. To further increase recording time, Sony introduced the AG-120 autochanger that would swap a second cassette into an SL-8200 for a maximum four hours. Autochangers continued to be a feature on Betamax into the early 80s.

Popular Science, November 1977

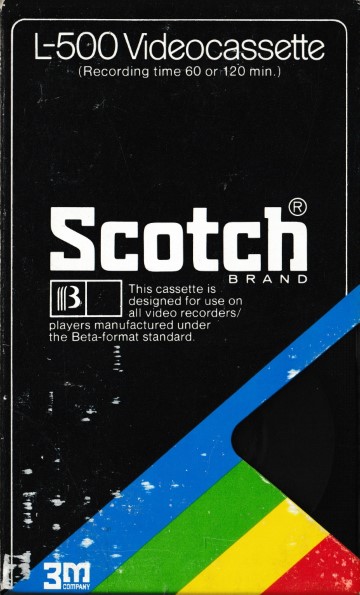

Companies that already were making magnetic tape also began producing Beta tapes, with Scotch producing their first tapes in the "K" series era. In time, many manufacturers who were only in the tape side of the business and did not make VCRs of their own supported both VHS and Beta, seeing both sides of the war as simply more people to sell tapes to. Sony themselves began selling VHS tapes in the early 80s.

The first inklings of commercial releases on both VHS and Beta came in 1977. Although tape trading and selling groups had existed since the late 60s for open reel machines, and Sony had announced a deal for prerecorded cassettes with Paramount in 1976, the first "commercial" Beta (and VHS) releases generally all date to around 1977. Far and away the most successful of these was Magnetic Video Corporation of Farmington Hills, Michigan, later known for their very iconic opening logo, who secured a deal with Fox to license fifty of their movies for VHS and Beta release. Andre Blay, co-founder of Magnetic Video Corporation, established the Video Club of America to sell these tapes to consumers. Although common home ownership of prerecorded cassettes was still a few years away, the video rental market began soon after when George Atkinson started the Video Station in Los Angeles by purchasing one each of every title on both format to rent out. Magnetic Video Corporation acquired the right to release other back catalogs on video tape from Viacom, Embassy, ABC, United Artists, and others, and was purchased by Fox in 1979 and eventually reorganized into 20th Century-Fox Video. All commercial Beta releases were recorded at the Beta II speed, which would quickly become the "standard" Beta speed, especially when Sony stopped supporting recording in Beta I on consumer Beta VCRs around 1978. Beta I did continue to be offered and supported for industrial uses, with many industrial Beta VCRs aimed at schools and businesses only supporting Beta I. By November of 1978, as many as 17 different firms offered prerecorded Betamax cassettes.

Allegedly, in 1977, 49% of the American public know what a "Betamax" was. In some places, "Betamax" became the name of a machine that records television much like "Walkman" became the name for a portable cassette player, and people would go into stores asking for "a VHS Betamax" for years to come. 50,000 Betamax decks had been sold in the US by April 1977. (Video Revue, Time)

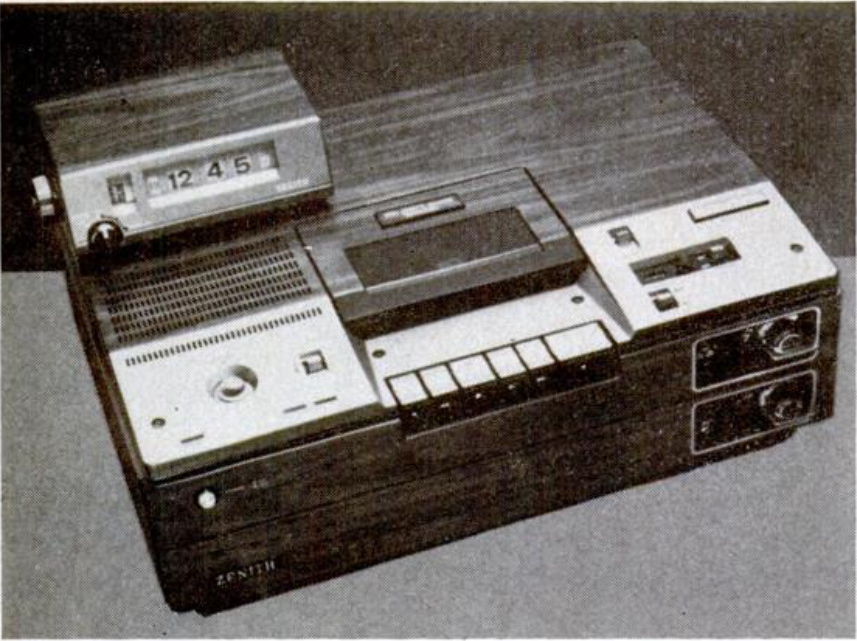

By 1978 other manufacturers started to produce their own Beta decks. Sanyo and Toshiba, having abandoned Sanyo's V-Cord format, brought out their early mechanical Beta VCRs, and Zenith had signed a deal with Sony to sell Sony built machines, beginning with a clone of the SL-8200 in late 1977. Many more manufacturers were getting into the VHS system, either producing their own recorders or rebadging others, including stores like Montgomery Ward.

Although both standards could be made by any company as long as they licensed the technology and implemented it correctly, Sony had higher licensing fees and ******

Early Beta VCRs generally used a loading ring similar to that of Umatic with a stationary head drum and rotating scanner containing two video heads. Generally Beta VCRs are laced whenever a cassette is inserted and remain that way even when fast forwarding or rewinding - or are switched off - unlike VHS VCRs which will often unlace for high speed winding or when not actively playing from the tape.

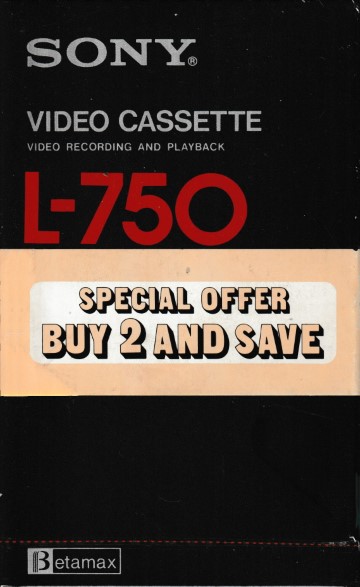

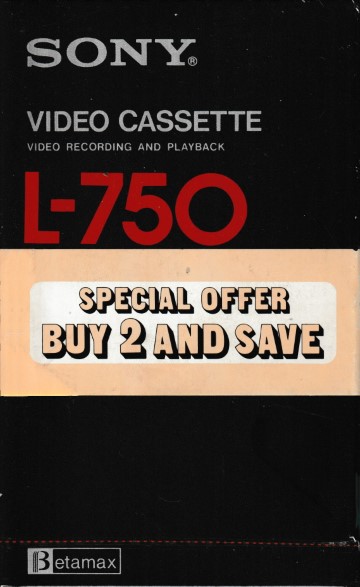

The L750 tape was introduced in Spring 1978 alongside the SL-8600, offering up to three hours on Beta's X2 speed. The new thinner tape was found to occasionally cause problems in existing Beta decks, and a warning was added to cassettes and in some publications.

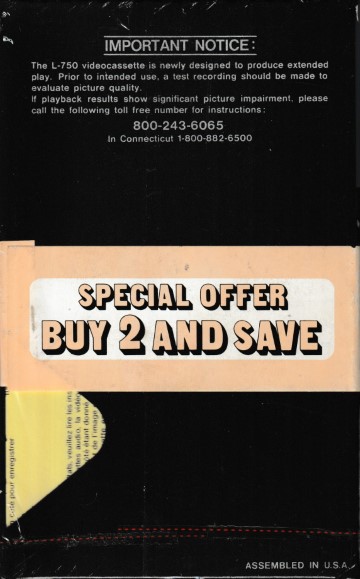

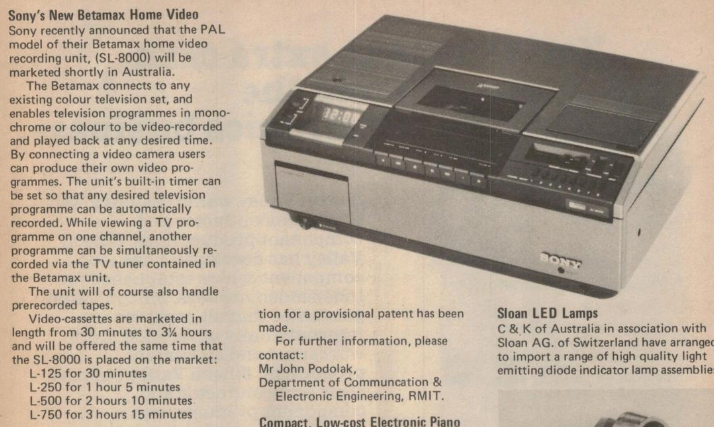

By the summer of 1978, Sony had begun distributing and marketing the SL-8000, their first PAL format Betamax, in Europe and Australia.

Electronics Today International, June 1978

In PAL territories, Betamax only had a single speed, with runtimes similar to the NTSC Beta II speed. An L-750 tape offered approximately 3 hours and 15 minutes of recording time on a PAL deck, compared with approximately three hours at Beta II speed on an NTSC machine (generally, all tapes, VHS and Beta, actually run for a few minutes longer than their quoted runtime).

By the end of 1978, VHS was outselling Beta two to one in America.

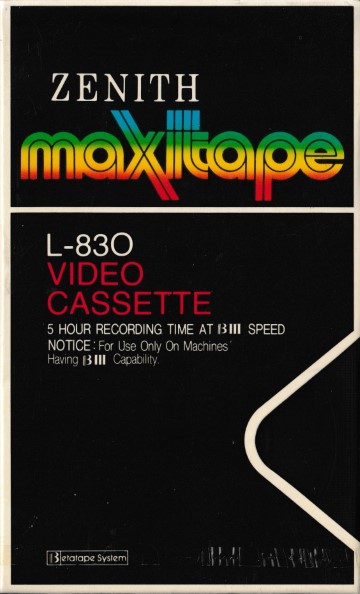

In the early days of the format war, Beta was a somewhat fractured format. While the format itself was "Beta," many manufacturers added their own suffixes to the Beta name - most famously, of course, Sony themselves, who called it Betamax. Sanyo referred to their Beta VCRs as Betacords,Toshiba as BetaVideo, Sears rebranded Sanyo and Toshiba Beta VCRs as BetaVision, and other companies like Zenith branded some of their players, made by Sony, as "Video Directors" and tapes as part of the "Betatape System." This led to some confusion in the marketplace in terms of compatibility. Sony sold their cassettes as Betamax for the first two generations, while other companies offered tapes with their own suffixes or the "Beta-square" generic mark with a notice about cassettes being compatible with the Beta format. The Beta symbol used at this time incorporated three vertical stripes in the downstroke that were shown in color on some of the VCRs. As new speeds were introduced to Beta, Sony retroactively called the original Beta I speed simply "Betamax," as their VCRs that recorded only in that speed would have been labeled, or X1, and the new speeds Betamax X2 (and briefly Betamax X3, on the SL-5400) before renaming them to the more familiar Beta I/II/III.

In ****, Sony ran this ad for the SL-****, which drew the ire of Universal Studios who in turn along with Disney and other film industry members sued Sony in what would become "Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc." or, simply, "the Betamax case," which would decide the legality of recording television broadcasts for the purposes of timeshifting.

In April of 1979, Sony released the PCM-1 processor, their first pulse-code modulation encoder roughly aimed at the home market, but with a hefty price tag of $4,400. PCM audio on video tape never really caught on for home use, although its use on audio CDs would prove a runaway success a few years later, and video tape based PCM processors would see use in audio recording studios and other industries where recording digital audio became common. A scant few dubbed-on-demand music releases were eventually released for home users on Beta, but were and remain expensive to buy. Although it would work with any video recorder, Sony recommended you use it with a Betamax or Umatic.

Popular Science, April 1979

Both Beta and VHS began with simple linear mono audio recording on the edge of the tape like a conventional audio tape recorder. This audio track was sufficient for general use and continued to be offered on basic VCRs of both formats until their ends. Beginning with the SL-J7 in Japan in 1979, Sony and a few other manufacturers like Toshiba offered Beta recorders with linear stereo. Linear stereo essentially fit two linear audio tracks in the same space previously used for the single mono track. If you know anything about what effects the quality of conventional audio tape recordings, you know that in general, the higher the speed the tape is moving at and the wider the recorded tracks are, the better the quality. Increased tape hiss and low frequency response plagued both format's linear stereo implementation, and to combat this noise reduction schemes like those previously implemented on audio tape were introduced. Sony called their system Beta Noise Reduction or Beta NR, while many linear stereo VHS machines used standard Dolby noise reduction just like audio cassettes. Both VHS and Beta linear stereo saw low American adoption rates, with few linear stereo Betas being released outside of Japan. Japan and a few European countries already had a broadcast stereo TV standard, typically used for simulcasting in multiple languages, but America had just begun to form a standardized stereo TV transmission method, and stereo TV would not become widespread in the US for several years. FM stereo simulcasts existed in the US by this time, but audio quality issues generally meant you were better off recording such audio broadcasts to cassette tape with a conventional tape recorder.

Sony offered several linear stereo VCRs in Japan like the *****, which, similar to many Sony personal stereos at the time, offered two headphone jacks built into the wired remote control.

In ****** 1979, the initial verdict in that "Betamax case" ruled that making individual copies of complete television shows was, in fact, fair use.

1980ssssss

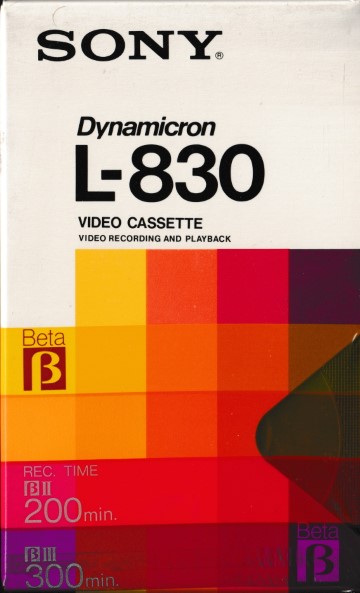

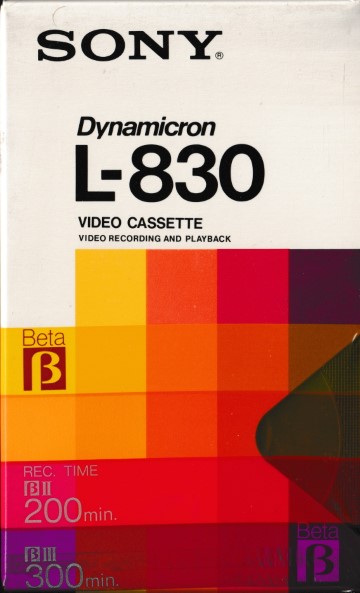

By the time the 80s rolled around, it was clear that Beta needed to standardize. Sony's new Dynamicron tapes and VCRs began using a refreshed Beta logo and deemphasized the Betamax name, with pretty much all manufacturers following the new unified logos and naming. The "X" naming scheme for tape speed had already been changed to the "Beta I/II/III" convention later in the original L series and starting on the *****, and throughout the 80s most consumer Beta VCRs would record and play only in Beta II and Beta III, with Sony machines usually offering Beta I playback only.

In an effort to make up for their runtime shortcomings, Beta format VCRs often were the first VCRs available to consumers with advanced recording and playback and "trick" features, with VHS usually catching up within a year. Some of these earlier features were aided by the fact that most Beta decks stayed laced - the tape was already traveling past all the normal heads of the machine whenever it was inserted or being wound. Picture search, called BetaScan by Sony, was first available on the *****. Prior to this, engaging fast forward or rewind would simply cut video output. Swing search, called BetaSkipScan, was engaged by holding fast forward or rewind again while in full speed fast forward or rewind and would drop the machine back into BetaScan and set it back into higher speed winding when released.. Some models, like the *****, offered variable speed BetaScan through an analog control on the wired remote. This feature would resurface later with the rise of the use of jog/shuttle dials on Beta VCRs, and was eventually implemented on VHS as well.

After the speed wars of the late 70s had concluded, both formats spent the 80s improving the quality of their recordings.

the betamax case

In 1983, Sanyo's VCR3900 became the first home VCR to sell for under $400 at introduction. Sanyo would continue (and already had been) making very affordable and pretty well built Beta VCRs.

Vidiot vol. 3

In July 1983 Sony introduced the BMC-100 Betamovie in Japan, the first true camcorder. Many portable VCR (and VTRs) were sold with wired cameras, but the Betamovie was the first true camcorder as we would know them today (er, yesterday). The Beta transport was miniaturized down to such a degree that it wasn't truly compatible - the head drum was smaller, and the tape wrapped more of the way around the head drum than on a Beta VCR. As a result, the Betamovie could not - physically could not - play back its own (or any other) tapes, so anyone who owned a Betamovie camcorder also needed a separate Beta VCR to play back what they had recorded. And people still bought them!

Around the same time, Sony also began bombarding the market with many variations of the E-Z Beta slimline VCRs, many of which started around 500 dollars. American VCR sales in 1983 were so feverish that many VHS sellers couldn't keep up with demand, and almost any VCR was selling, including Sony's cheap Betas.

top gun, et on home video, porn

In 1984, through sales of decks like more inexpensive Beta VCRs like the ***** toploader, also sold rebadged at Sears, Sanyo actually became the largest manufacturer and seller of Beta in the United States. Sanyo was making VHS VCRs for Fisher and Radio Shack, but did not sell them under their own name.

While linear stereo wasn't going to catch the attention of any audiophiles, the same helical scanning method that made video tape recording viable also brought high fidelity audio to Beta. Beta hi-fi embedded stereo audio into the picture signal, producing mostly backwards compatible recordings. Sony figured that VHS couldn't copy this, and they were partiallty right - Beta hi-fi didn't use any extra heads on the head drum to record and play back the audio tracks. VHS hifi couldn't do this neat trick and needed extra heads added to the drum to accomplish hifi audio, but did so nonetheless. All hifi VCRs were backwards compatible with linear mono machines, still including and recording with the required linear audio head as part of the tracking and control head, and most could be set to only record in mono or to do "tricks" like mixing the mono and hifi tracks, playing only one channel or the other, or recording different audio to the hifi and linear tracks. This feature in particular was typically used for simulcast recordings, typically either an FM stereo broadcast of the audio of a televised concert or music program that was picked up with a standard external FM radio receiver and fed into the VCR's stereo inputs or an alternate language track that could be tuned separately. Some Japanese tuners and VCRs could pick up bilingual transmissions of dubbed movies and allowed you to listen to either the original audio or the Japanese dub (or, indeed, both) by switching between the left or right hifi channels.

One slight drawback to both hifi systems was that they could not be overdubbed later. Unlike the linear audio tracks, which could be recorded separately from the video signal along the endge of the tape, hifi sound was "embedded" into the helical video picture information and could not be overwritten later without also recording over the video signal. Audio dubbing had been and continued to be available on some VCRs, which would simply run the video head drum in playback mode so you could see what you were overdubbing while it recorded your audio input from a microphone or other external source over the original linear audio, leaving the video intact. hifi audio dubbing typically required a second VCR. The source tape would be played on one VCR and recorded on another, with the recording VCR having its audio input set to the new audio source.

In 1985, Sony introduced SuperBeta VCRs, which offered increased (luma or chroma?) bandwidth

In Japan this system was referred to as Hi-Band recording, and SuperBeta machines were called Hi-Band Beta.

In mid-April 1985, Toshiba announced that, like they were already doing in Japan and Europe, they would sell a VHS deck in the American market., advertising it as the first VHS to stack up to their Beta hi-fi *****. Sanyo was also selling VHS machines in Japan and OEM'ed them to Radio Shack and other distributers, and Pioneer would begin selling a Hitachi made VHS VCR alongside their Sony Beta and 8mm equipment. VHS was outselling Betamax approximately four to one by 1985.

Later in 1985, Sony announced that all future Beta VCRs would be SuperBeta. (Video Magazine, September 1985)

betamovie

The first stab at countering SueprBeta by the VHS manufacturers was VHS High Quality, or HQ, but the standard ended up being relaxed to be cheaper to manufacture. The true SuperBeta competitior, Super VHS, debuted in 1987. More information about both of these systems is available on the VHS history page. Sony sold the system as being backwards compatible with normal Beta VCRs, and while the systems are mostly interchangeable, some SuperBeta recordings would produce an effect that looked like tape dropouts on non-SuperBeta VCRs.

An interesting side effect of using the normal heads for Beta hi-fi is that it let Sony make "upgradable" VCRs. Sold as "hifi Ready," or Beta Plus in Japan, Sony released a number of monophonic Beta VCRs and a single mono SuperBeta VCR with a multi-pin connector on the back that would plug into an external stereo decoder box that provided hifi inputs and outputs and related controls. This was an interesting marketing idea, and presumably kept costs somewhat down for both Sony and consumers, but the idea died off by ****. For more detailed information, visit the hifi Ready Beta page.

In **** Sony again pushed the boundaries of their SuperBeta technique by offering what was called Super Hi-Band recording capabilities. These modes only worked at the old Beta I speed, which was brought back as a recording option in the new Super Hi-Band mode only as Beta Is. The original version increased bandwith to 5.6MHz and was referred to as Super Hi-Band Beta Is, or, after the introduction of the 6MHz variation on the ***** in ****, 5.6MHz Super Hi-Band Beta Is. These recordings (were not compatible with older VCRs, producing a *******). This system saw limited adoption, particularly in the US. These systems were called Super Hi-Band in the US and other regions where the original Japanese Hi-Band system had already been known as SuperBeta, creating an odd symmetry in the naming scheme where the region that was originally Hi-Band gained Super and the region that originally had Super gained Hi-Band. Only one Beta not built by Sony, NEC's VC-N65EU, offered Beta Is recording capabilities.

Sony tried once again in 1988 to upgrade Beta's picture quality with their new Extended Definition, or ED, Betas. ED Beta used metal particle tapes to squeeze additional resolution out of the Beta system. ED Beta VCRs all offer S-video inputs and outputs and were all also capable of playing hifi, Super, and usually 5.6MHz Super Hi-Band recordings as well.

S-video output was uncommon on non-ED Beta decks, but was available on the *******

Sony functionally admitted defeat on ******, 1988 when they released a press statement saying that they would begin to sell VHS VCRs, at first ones rebranded from *****. There had been a permuating rumor that this was the case for some months, with Sony denying such rumors right up to the time of the press release.

Unfortunately, with the end of the 80s came the end of the true heyday of Betamax. After the top of the line ED Beta EDV-9000 in 1989 and the buttonless 15th anniversary SL-2100 Betamax in 1990, Sony released scant few Beta machines throughout the 90s, with most being stripped-down versions of previous models. While Sony experimented with funky combination VHS and 8mm or DV VCRs throughout the 90s, machines like 1997's SL-F205 were generally mid-range units that offered nothing new or exciting.

By 1993, three quarters of American homes had a VCR, 99% of which were VHS.

Sony discontinued production of their Betamax video recorders in 2002.

Much like audio tape before it, it was clear that for widespread video tape adoption tape needed to be contained and easy to load and use, and by the late 60s Sony had developed a prototype of their Umatic video cassette system, with shippable units hitting the market in 1971. Sony did have hopes that this format would see consumer use early on, with tuner and timer options available for early machines, but the units were larger and more expensive than open reel video recorders and saw limited home adoption. For more about Umatic and its place in broadcast and industrial use, visit the Umatic page.

In the summer of 1974 Sony demoed their first working Betamax prototype. The format war began shortly after when Sony met with JVC and Matsushita to convince them to adopt Betamax, demonstrating the prototype to them later that year, while JVC and Matsushita continued to develop VHS

Early word about the new system appeared in American publications in early 1975, with a supposed price tag of $2,500 dollars for the unit built into a TV console, about twice the price of an institutional Umatic deck. Apparently, Sony also tried pitching the VCR to RCA around the same time, but RCA was still busy working on SelectaVision MagTape, as they had been for the last three years, which they were hoping to have out in 1976. Around this time, old Cartrivision "fishtank" mechanisms, the tape mechanisms of the failed early 70s video tape format, were being sold off for $300, and you were responsible for wiring it to your TV.

Sony introduced the LV-1801 console and SL-6300 standalone units in Japan in the summer of 1975. The standalone machine had no internal tuner or timer, using the same TT series of tuner-timers as was used for Umatic VCRs. These machines did not have a standard RF output built in, and Sony would install a video input jack to hook an SL-6300 up to their existing Trinitron sets.

photo source

In November 1975 the LV-6300, TT-100, and a Sony Trinitron television were packaged together and made for the first Beta offering for the US market, the LV-1901, debuting at $2295. The VCR portion was referred to as the SL-6200. The television and Umatic timer had separate tuners, allowing you to watch one channel and record another at the same time. The horizontal resolution was quoted at "more than 240 lines," up to 280 in black and white, and had a 3MHz bandwidth. Unsurprisingly, the high price tag and the fact that purchasing one required also wanting a new television did not make it an immediate success, but standalone models like the SL-7200, based on the Japanese SL-7300, quickly became available.

This early in the video format war it was not clearly a Betamax-VHS race. Several other formats entered the Japanese and American markets before VHS. Some companies were still making open reel VTRs or mostly forgotten cartridge formats like the Sanyo V-Cord II and the VX system, both of which saw very limited adoption even relative to early Beta machines, and for a short time in 1976 the format war was between Sony producing the Betamax, National producing the VX system, which was marketed in the US by Quasar as the "Great Time Machine," and Sanyo's V-Cord II which Toshiba had announced support for early on. These machines generally had built-in "knob" style tuners with the option for external timers and, before the introduction of the SL-8200, could record longer than Betamax, with V-Cord II offering up to two hours in skip-field mode and 120 minute cartridges for the VX system selling for $34. One hour cartridge were $19, about three dollars more than a Sony K60 at the time. The VX system saw limited adoption, although the V-Cord II saw some industrial use. Both major early video disc systems had been in development for some time by this point, but the earliest DiscoVision players wouldn't be out for another year, with RCA's CED taking even longer. More information about the developments of these systems is available on the Video disc page.

At introduction Sony offered two tape lengths under the "K" series, the K30 and K60. The K60 cassette retailed for $15.95 and the K30 at $11.95 at introduction. Like the names suggest, these offered 30 and 60 minutes of runtime respectively, the same lengths that Sony had been producing open reel video tape at for a decade and similar to the availability of Umatic tapes at the time. When VHS debuted in the US in late 1977 with a two hour base runtime and many early models supporting the long-play recording mode that offered up to four hours on a standard tape - for around $1000 - it was clear Sony needed to increase their record times, and soon after released the SL-8200, the first American two speed Beta, based on the Japanese SL-8100 and SL-8300 Beta I and II VCRs that had been released in Japan earlier that year.

In 1977 the K series tapes began to be replaced with the new L series of tapes. Unlike the simple 30 or 60 designating runtime like the T120 standard of VHS, the L series tapes used a rounded measure of their length in feet as the basis for their numbering scheme which gave no obvious indication of their actual recording length. To further increase recording time, Sony introduced the AG-120 autochanger that would swap a second cassette into an SL-8200 for a maximum four hours. Autochangers continued to be a feature on Betamax into the early 80s.

Popular Science, November 1977

Companies that already were making magnetic tape also began producing Beta tapes, with Scotch producing their first tapes in the "K" series era. In time, many manufacturers who were only in the tape side of the business and did not make VCRs of their own supported both VHS and Beta, seeing both sides of the war as simply more people to sell tapes to. Sony themselves began selling VHS tapes in the early 80s.

The first inklings of commercial releases on both VHS and Beta came in 1977. Although tape trading and selling groups had existed since the late 60s for open reel machines, and Sony had announced a deal for prerecorded cassettes with Paramount in 1976, the first "commercial" Beta (and VHS) releases generally all date to around 1977. Far and away the most successful of these was Magnetic Video Corporation of Farmington Hills, Michigan, later known for their very iconic opening logo, who secured a deal with Fox to license fifty of their movies for VHS and Beta release. Andre Blay, co-founder of Magnetic Video Corporation, established the Video Club of America to sell these tapes to consumers. Although common home ownership of prerecorded cassettes was still a few years away, the video rental market began soon after when George Atkinson started the Video Station in Los Angeles by purchasing one each of every title on both format to rent out. Magnetic Video Corporation acquired the right to release other back catalogs on video tape from Viacom, Embassy, ABC, United Artists, and others, and was purchased by Fox in 1979 and eventually reorganized into 20th Century-Fox Video. All commercial Beta releases were recorded at the Beta II speed, which would quickly become the "standard" Beta speed, especially when Sony stopped supporting recording in Beta I on consumer Beta VCRs around 1978. Beta I did continue to be offered and supported for industrial uses, with many industrial Beta VCRs aimed at schools and businesses only supporting Beta I. By November of 1978, as many as 17 different firms offered prerecorded Betamax cassettes.

Allegedly, in 1977, 49% of the American public know what a "Betamax" was. In some places, "Betamax" became the name of a machine that records television much like "Walkman" became the name for a portable cassette player, and people would go into stores asking for "a VHS Betamax" for years to come. 50,000 Betamax decks had been sold in the US by April 1977. (Video Revue, Time)

By 1978 other manufacturers started to produce their own Beta decks. Sanyo and Toshiba, having abandoned Sanyo's V-Cord format, brought out their early mechanical Beta VCRs, and Zenith had signed a deal with Sony to sell Sony built machines, beginning with a clone of the SL-8200 in late 1977. Many more manufacturers were getting into the VHS system, either producing their own recorders or rebadging others, including stores like Montgomery Ward.

Although both standards could be made by any company as long as they licensed the technology and implemented it correctly, Sony had higher licensing fees and ******

Early Beta VCRs generally used a loading ring similar to that of Umatic with a stationary head drum and rotating scanner containing two video heads. Generally Beta VCRs are laced whenever a cassette is inserted and remain that way even when fast forwarding or rewinding - or are switched off - unlike VHS VCRs which will often unlace for high speed winding or when not actively playing from the tape.

The L750 tape was introduced in Spring 1978 alongside the SL-8600, offering up to three hours on Beta's X2 speed. The new thinner tape was found to occasionally cause problems in existing Beta decks, and a warning was added to cassettes and in some publications.

By the summer of 1978, Sony had begun distributing and marketing the SL-8000, their first PAL format Betamax, in Europe and Australia.

Electronics Today International, June 1978

In PAL territories, Betamax only had a single speed, with runtimes similar to the NTSC Beta II speed. An L-750 tape offered approximately 3 hours and 15 minutes of recording time on a PAL deck, compared with approximately three hours at Beta II speed on an NTSC machine (generally, all tapes, VHS and Beta, actually run for a few minutes longer than their quoted runtime).

By the end of 1978, VHS was outselling Beta two to one in America.

In the early days of the format war, Beta was a somewhat fractured format. While the format itself was "Beta," many manufacturers added their own suffixes to the Beta name - most famously, of course, Sony themselves, who called it Betamax. Sanyo referred to their Beta VCRs as Betacords,Toshiba as BetaVideo, Sears rebranded Sanyo and Toshiba Beta VCRs as BetaVision, and other companies like Zenith branded some of their players, made by Sony, as "Video Directors" and tapes as part of the "Betatape System." This led to some confusion in the marketplace in terms of compatibility. Sony sold their cassettes as Betamax for the first two generations, while other companies offered tapes with their own suffixes or the "Beta-square" generic mark with a notice about cassettes being compatible with the Beta format. The Beta symbol used at this time incorporated three vertical stripes in the downstroke that were shown in color on some of the VCRs. As new speeds were introduced to Beta, Sony retroactively called the original Beta I speed simply "Betamax," as their VCRs that recorded only in that speed would have been labeled, or X1, and the new speeds Betamax X2 (and briefly Betamax X3, on the SL-5400) before renaming them to the more familiar Beta I/II/III.

In ****, Sony ran this ad for the SL-****, which drew the ire of Universal Studios who in turn along with Disney and other film industry members sued Sony in what would become "Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc." or, simply, "the Betamax case," which would decide the legality of recording television broadcasts for the purposes of timeshifting.

In April of 1979, Sony released the PCM-1 processor, their first pulse-code modulation encoder roughly aimed at the home market, but with a hefty price tag of $4,400. PCM audio on video tape never really caught on for home use, although its use on audio CDs would prove a runaway success a few years later, and video tape based PCM processors would see use in audio recording studios and other industries where recording digital audio became common. A scant few dubbed-on-demand music releases were eventually released for home users on Beta, but were and remain expensive to buy. Although it would work with any video recorder, Sony recommended you use it with a Betamax or Umatic.

Popular Science, April 1979

Both Beta and VHS began with simple linear mono audio recording on the edge of the tape like a conventional audio tape recorder. This audio track was sufficient for general use and continued to be offered on basic VCRs of both formats until their ends. Beginning with the SL-J7 in Japan in 1979, Sony and a few other manufacturers like Toshiba offered Beta recorders with linear stereo. Linear stereo essentially fit two linear audio tracks in the same space previously used for the single mono track. If you know anything about what effects the quality of conventional audio tape recordings, you know that in general, the higher the speed the tape is moving at and the wider the recorded tracks are, the better the quality. Increased tape hiss and low frequency response plagued both format's linear stereo implementation, and to combat this noise reduction schemes like those previously implemented on audio tape were introduced. Sony called their system Beta Noise Reduction or Beta NR, while many linear stereo VHS machines used standard Dolby noise reduction just like audio cassettes. Both VHS and Beta linear stereo saw low American adoption rates, with few linear stereo Betas being released outside of Japan. Japan and a few European countries already had a broadcast stereo TV standard, typically used for simulcasting in multiple languages, but America had just begun to form a standardized stereo TV transmission method, and stereo TV would not become widespread in the US for several years. FM stereo simulcasts existed in the US by this time, but audio quality issues generally meant you were better off recording such audio broadcasts to cassette tape with a conventional tape recorder.

Sony offered several linear stereo VCRs in Japan like the *****, which, similar to many Sony personal stereos at the time, offered two headphone jacks built into the wired remote control.

In ****** 1979, the initial verdict in that "Betamax case" ruled that making individual copies of complete television shows was, in fact, fair use.

1980ssssss

By the time the 80s rolled around, it was clear that Beta needed to standardize. Sony's new Dynamicron tapes and VCRs began using a refreshed Beta logo and deemphasized the Betamax name, with pretty much all manufacturers following the new unified logos and naming. The "X" naming scheme for tape speed had already been changed to the "Beta I/II/III" convention later in the original L series and starting on the *****, and throughout the 80s most consumer Beta VCRs would record and play only in Beta II and Beta III, with Sony machines usually offering Beta I playback only.

In an effort to make up for their runtime shortcomings, Beta format VCRs often were the first VCRs available to consumers with advanced recording and playback and "trick" features, with VHS usually catching up within a year. Some of these earlier features were aided by the fact that most Beta decks stayed laced - the tape was already traveling past all the normal heads of the machine whenever it was inserted or being wound. Picture search, called BetaScan by Sony, was first available on the *****. Prior to this, engaging fast forward or rewind would simply cut video output. Swing search, called BetaSkipScan, was engaged by holding fast forward or rewind again while in full speed fast forward or rewind and would drop the machine back into BetaScan and set it back into higher speed winding when released.. Some models, like the *****, offered variable speed BetaScan through an analog control on the wired remote. This feature would resurface later with the rise of the use of jog/shuttle dials on Beta VCRs, and was eventually implemented on VHS as well.

After the speed wars of the late 70s had concluded, both formats spent the 80s improving the quality of their recordings.

the betamax case

In 1983, Sanyo's VCR3900 became the first home VCR to sell for under $400 at introduction. Sanyo would continue (and already had been) making very affordable and pretty well built Beta VCRs.

Vidiot vol. 3

In July 1983 Sony introduced the BMC-100 Betamovie in Japan, the first true camcorder. Many portable VCR (and VTRs) were sold with wired cameras, but the Betamovie was the first true camcorder as we would know them today (er, yesterday). The Beta transport was miniaturized down to such a degree that it wasn't truly compatible - the head drum was smaller, and the tape wrapped more of the way around the head drum than on a Beta VCR. As a result, the Betamovie could not - physically could not - play back its own (or any other) tapes, so anyone who owned a Betamovie camcorder also needed a separate Beta VCR to play back what they had recorded. And people still bought them!

Around the same time, Sony also began bombarding the market with many variations of the E-Z Beta slimline VCRs, many of which started around 500 dollars. American VCR sales in 1983 were so feverish that many VHS sellers couldn't keep up with demand, and almost any VCR was selling, including Sony's cheap Betas.

top gun, et on home video, porn

In 1984, through sales of decks like more inexpensive Beta VCRs like the ***** toploader, also sold rebadged at Sears, Sanyo actually became the largest manufacturer and seller of Beta in the United States. Sanyo was making VHS VCRs for Fisher and Radio Shack, but did not sell them under their own name.

While linear stereo wasn't going to catch the attention of any audiophiles, the same helical scanning method that made video tape recording viable also brought high fidelity audio to Beta. Beta hi-fi embedded stereo audio into the picture signal, producing mostly backwards compatible recordings. Sony figured that VHS couldn't copy this, and they were partiallty right - Beta hi-fi didn't use any extra heads on the head drum to record and play back the audio tracks. VHS hifi couldn't do this neat trick and needed extra heads added to the drum to accomplish hifi audio, but did so nonetheless. All hifi VCRs were backwards compatible with linear mono machines, still including and recording with the required linear audio head as part of the tracking and control head, and most could be set to only record in mono or to do "tricks" like mixing the mono and hifi tracks, playing only one channel or the other, or recording different audio to the hifi and linear tracks. This feature in particular was typically used for simulcast recordings, typically either an FM stereo broadcast of the audio of a televised concert or music program that was picked up with a standard external FM radio receiver and fed into the VCR's stereo inputs or an alternate language track that could be tuned separately. Some Japanese tuners and VCRs could pick up bilingual transmissions of dubbed movies and allowed you to listen to either the original audio or the Japanese dub (or, indeed, both) by switching between the left or right hifi channels.

One slight drawback to both hifi systems was that they could not be overdubbed later. Unlike the linear audio tracks, which could be recorded separately from the video signal along the endge of the tape, hifi sound was "embedded" into the helical video picture information and could not be overwritten later without also recording over the video signal. Audio dubbing had been and continued to be available on some VCRs, which would simply run the video head drum in playback mode so you could see what you were overdubbing while it recorded your audio input from a microphone or other external source over the original linear audio, leaving the video intact. hifi audio dubbing typically required a second VCR. The source tape would be played on one VCR and recorded on another, with the recording VCR having its audio input set to the new audio source.

In 1985, Sony introduced SuperBeta VCRs, which offered increased (luma or chroma?) bandwidth

In Japan this system was referred to as Hi-Band recording, and SuperBeta machines were called Hi-Band Beta.

In mid-April 1985, Toshiba announced that, like they were already doing in Japan and Europe, they would sell a VHS deck in the American market., advertising it as the first VHS to stack up to their Beta hi-fi *****. Sanyo was also selling VHS machines in Japan and OEM'ed them to Radio Shack and other distributers, and Pioneer would begin selling a Hitachi made VHS VCR alongside their Sony Beta and 8mm equipment. VHS was outselling Betamax approximately four to one by 1985.

Later in 1985, Sony announced that all future Beta VCRs would be SuperBeta. (Video Magazine, September 1985)

betamovie

The first stab at countering SueprBeta by the VHS manufacturers was VHS High Quality, or HQ, but the standard ended up being relaxed to be cheaper to manufacture. The true SuperBeta competitior, Super VHS, debuted in 1987. More information about both of these systems is available on the VHS history page. Sony sold the system as being backwards compatible with normal Beta VCRs, and while the systems are mostly interchangeable, some SuperBeta recordings would produce an effect that looked like tape dropouts on non-SuperBeta VCRs.

An interesting side effect of using the normal heads for Beta hi-fi is that it let Sony make "upgradable" VCRs. Sold as "hifi Ready," or Beta Plus in Japan, Sony released a number of monophonic Beta VCRs and a single mono SuperBeta VCR with a multi-pin connector on the back that would plug into an external stereo decoder box that provided hifi inputs and outputs and related controls. This was an interesting marketing idea, and presumably kept costs somewhat down for both Sony and consumers, but the idea died off by ****. For more detailed information, visit the hifi Ready Beta page.

In **** Sony again pushed the boundaries of their SuperBeta technique by offering what was called Super Hi-Band recording capabilities. These modes only worked at the old Beta I speed, which was brought back as a recording option in the new Super Hi-Band mode only as Beta Is. The original version increased bandwith to 5.6MHz and was referred to as Super Hi-Band Beta Is, or, after the introduction of the 6MHz variation on the ***** in ****, 5.6MHz Super Hi-Band Beta Is. These recordings (were not compatible with older VCRs, producing a *******). This system saw limited adoption, particularly in the US. These systems were called Super Hi-Band in the US and other regions where the original Japanese Hi-Band system had already been known as SuperBeta, creating an odd symmetry in the naming scheme where the region that was originally Hi-Band gained Super and the region that originally had Super gained Hi-Band. Only one Beta not built by Sony, NEC's VC-N65EU, offered Beta Is recording capabilities.

Sony tried once again in 1988 to upgrade Beta's picture quality with their new Extended Definition, or ED, Betas. ED Beta used metal particle tapes to squeeze additional resolution out of the Beta system. ED Beta VCRs all offer S-video inputs and outputs and were all also capable of playing hifi, Super, and usually 5.6MHz Super Hi-Band recordings as well.

S-video output was uncommon on non-ED Beta decks, but was available on the *******

Sony functionally admitted defeat on ******, 1988 when they released a press statement saying that they would begin to sell VHS VCRs, at first ones rebranded from *****. There had been a permuating rumor that this was the case for some months, with Sony denying such rumors right up to the time of the press release.

Unfortunately, with the end of the 80s came the end of the true heyday of Betamax. After the top of the line ED Beta EDV-9000 in 1989 and the buttonless 15th anniversary SL-2100 Betamax in 1990, Sony released scant few Beta machines throughout the 90s, with most being stripped-down versions of previous models. While Sony experimented with funky combination VHS and 8mm or DV VCRs throughout the 90s, machines like 1997's SL-F205 were generally mid-range units that offered nothing new or exciting.

By 1993, three quarters of American homes had a VCR, 99% of which were VHS.

Sony discontinued production of their Betamax video recorders in 2002.